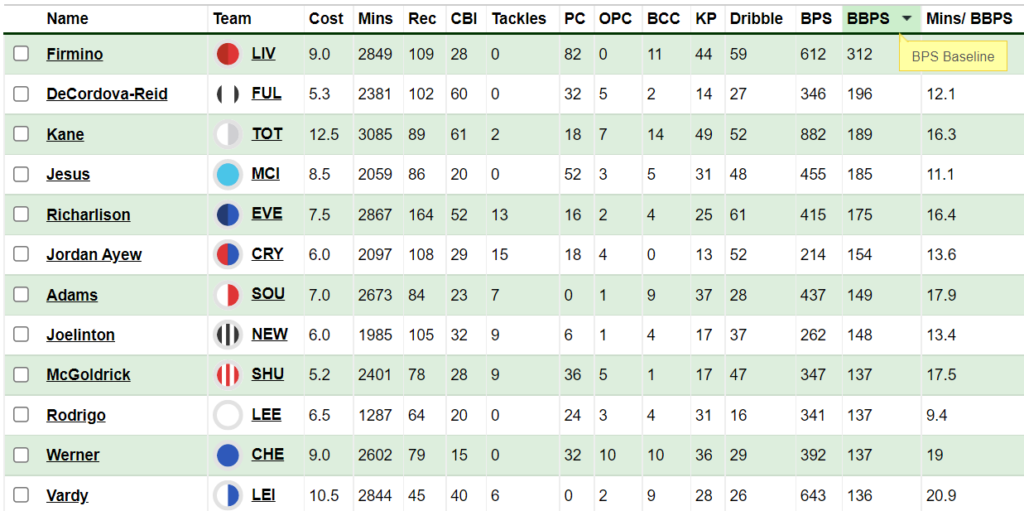

Fantasy Football Scout regular TopMarx continues his multi-part series on one of the most hotly discussed facets of Fantasy Premier League: its Bonus Points System (BPS).

We have already heard about the history of BPS and how Opta ‘sees’ games in parts one and two of this discussion.

And don’t forget that you can see all manner of bonus point information in our Player Stats and Matches tabs in the Premium Members Area, an example of which is shown below.

Opta Sports is the brainchild of one woman.

Back in the summer of 1996 a group of management consultants employed marketing executive Suzie Russell to raise the profile of their new enterprise, Opta Consulting.

A fanatical Southampton fan, Russell came up with the idea of a player performance index for football.

She took inspiration from her employer’s previous company, Coopers & Lybrand Deloitte (later PricewaterhouseCoopers), who had created the first cricket ratings and generated a phenomenal amount of publicity for the accountancy firm.

The Opta Index was up and running in just five weeks. In that time, Russell had persuaded the Premier League and Sky Sports to back the idea, and hired former England coach Don Howe to develop the system.

Many of the stats from those early days are still the same today.

Perhaps more remarkable is the similarity to the method used by the father of football analytics, Charles Reep, who annotated his first match in 1950:

The continuous action of a game is broken down into a series of discrete on-the-ball events (such as a pass, a centre or a shot) and a detailed categorization made for each type of event.

– Charles Reep, Skill and Chance in Association Football

An accountant with a passion for football, Reep was the first person to create a comprehensive notational system for the beautiful game. During his lifetime he would document nearly 2,500 matches by hand. The reason, in his words, was to:

…provide a counter to reliance upon memory, tradition and personal impressions that led to speculation and soccer ideologies.

– Charles Reep

Don’t be fooled; Reep may have used the word ‘soccer’ but not because he was American.

‘Soccer’ was common in the United Kingdom until the 1970s and featured in news reports of the time. It was originally a slang term for assoc., itself an abbreviation of association, in the same way that ‘rugger’ was used for rugby.

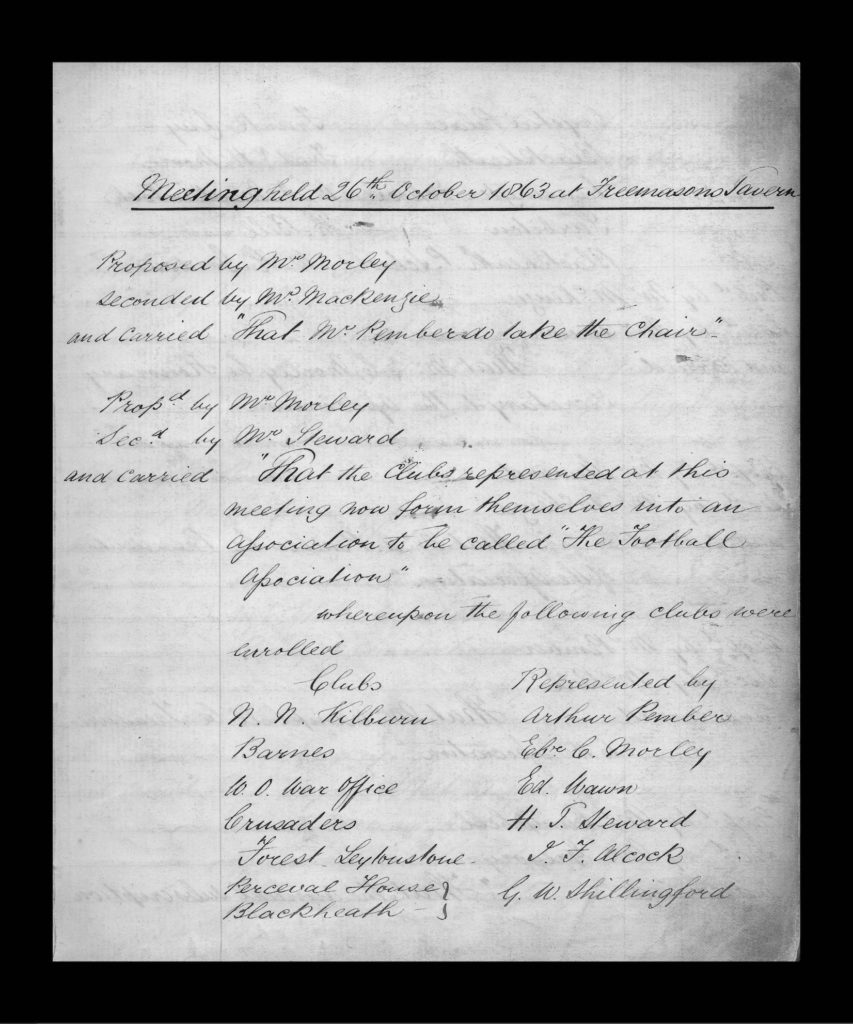

Even the word ‘football’ didn’t necessarily mean, as we might think, a ‘foot kicking a ball’. Instead, it may have referred to a ball game played on foot as opposed to on horseback. It also showed that “football belonged to the commoners; only the nobility could afford to use horses for games!”

The original minute that records the formation of the Football Association

It’s somewhat ironic, then, that the rules for association football were developed by the middle and upper classes.

During the mid-nineteenth century there were several codes in use: Sheffield, Cambridge, and the public schools such as Eton, Rugby and Harrow all had their own versions of the game.

The Football Association was formed with the aim of establishing a single unifying code. Although early drafts of its rules had more in common with modern-day rugby: throw-ins taken at right-angles, as a lineout is today; a goal scored when the ball “passes over the space between the goal posts (at whatever height)”; and a player deemed offside if he is in front of the ball.

The most disputed elements, however, allowed running with the ball in hands and ‘hacking’: kicking an adversary on the front of the leg below the knee. Although, mercifully, holding and hacking at the same time wasn’t permitted.

These two divisive laws were rather controversially removed from the final set drawn up in 1863, leading to several clubs withdrawing from the FA. As Bill Murray recounts:

The Blackheath club wanted to retain hacking, claiming that its abolition threatened the very “manliness” of football, and sneered that such sissy reforms would reduce the game to something more suited to the French.

– Bill Murray, “The World’s Game, A History of Soccer”

A Modern Challenge

On the 150th anniversary of the Football Association Opta became part of the Perform Group, who also used to run the sports streaming service DAZN.

The two entities remained under the same roof until they were split in 2019 with owner Sir Len Blavatnik harbouring desires to turn DAZN into a ‘Netflix of sport’.

In order to raise funds for this ambitious project, Perform Content was sold to US sports data specialist STATS to create Stats Perform.

In a roundabout way this merger affected Fantasy managers because ‘Attempted Tackles’ was added to Opta’s event list, and this redefined how some ‘Take Ons’ and ‘Challenges’ were recorded. Sadly it did not mean that hacking had made a comeback.

An ‘Attempted Tackle’ is similar to a ‘Challenge’ – but it’s not a duel event so there’s no corresponding attacking action.

In part two we learned that there’s always a balance of attacking and defensive actions with each ‘Take On’: for each successful ‘Take On’, when a player is dribbled past, the beaten man is logged as having made a ‘Challenge’.

A player unsuccessfully attempts to tackle an opponent, making no contact with the ball as the opponent dribbles past them.

– Opta definition of a ‘Challenge’

An ‘Attempted Tackle’ is when a player has tried to win the ball from a more stationary opponent, not a situation where he has been dribbled past.

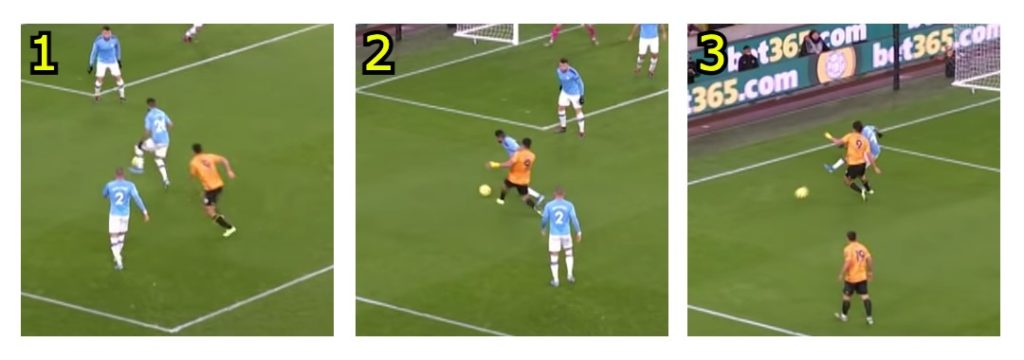

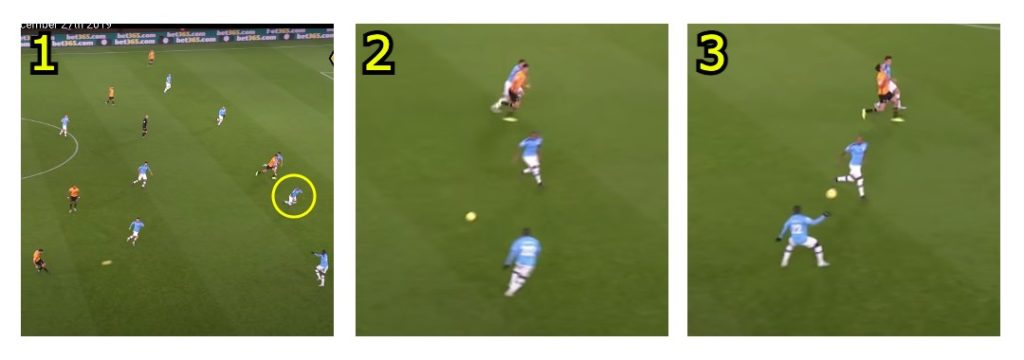

Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Manchester City 2019/20

(see video link to Wolves YouTube channel)

Diogo Jota receives a pass in midfield with Kevin De Bruyne bearing down on him (image 1), he turns as De Bruyne attempts to win the ball (image 2), but Jota successfully holds off the Belgian (image 3).

At the time, this was recorded as a ‘Challenge’ from De Bruyne and a successful ‘Take On’ from Jota. But today, because Jota wasn’t attempting to beat De Bruyne, it would simply be logged as an ‘Attempted Tackle’ by De Bruyne.

Jota would not be credited for keeping possession.

Last season, largely due to this change, there was a nine per cent reduction in the number of successful dribbles.

On the surface this is no bad thing: the most-successful dribblers are predominantly wingers and centre forwards, who tend to do fairly well in the Bonus Points System.

But the balance of the BPS is affected: players lose a point when they are tackled but gain a point each time they beat an opponent – and for the player tackled, there’s been no change in the way the stats are recorded.

Wilfried Zaha is an example of a winger who doesn’t do particularly well when it comes to bonus points: his successful dribbles are outweighed by the number of times he’s tackled. From 2015/16, no player has been tackled more than Zaha.

Compare Zaha’s 2019/20 season with that of Adama Traoré’s. Both players scored four goals but Traoré picked up 14 bonus points to Zaha’s four. Traoré did supply three more assists than Zaha, which undoubtedly made a difference, but Traoré is also much harder to tackle.

The Wolves winger made 183 successful dribbles and was tackled just 128 times throughout the campaign. Zaha also impressed with 163 successful dribbles, but he was far easier to dispossess, tackled on a whopping 252 occasions.

These totals mean that when it comes to their BPS score, Zaha made a net loss of 89 points whereas Traoré gained 55, a difference of 144. This surely goes some way to explaining why Zaha picked up fewer bonus points.

Another example is Eden Hazard and Mohamed Salah.

Before Traoré, Hazard was the best dribbler in the Premier League.

From 2016/17 to when he left Chelsea, Hazard beat his man 445 times and was tackled on 368 occasions. Over those three seasons he scored 44 goals, supplied 30 assists and picked up 92 bonus points.

Contrast that with Salah, a less effective dribbler, who in his first three years at Liverpool made 159 successful take ons but was dispossessed 333 times.

Despite scoring nearly twice as many goals as Hazard (80 to 44) and getting more assists (34 to 30), he received 22 fewer bonus points.

Minus Points

There’s lots at play in the BPS, as mentioned in parts one and two, but being tackled – because of its frequency – is the single biggest factor that will reduce a player’s likelihood of gaining performance-related marks.

Frequency of Bonus Point Events multiplied by Points

(click on image to enlarge)

Turning a Negative into a Positive

Despite having an impact on the Bonus Points System, the addition of ‘Attempted Tackles’ is definitely a good thing when it comes to accurately capturing the story of the match.

There is a clear difference between dribbling past and beating an opponent, as Traoré does frequently (example 1, example 2, example 3) and the attempted tackle by De Bruyne on Jota.

In one, the impetus comes from the attacking player, in the other it’s the defensive player.

There’s a sense that an ‘Attempted Tackle’ applies pressure to the man in possession whereas a ‘Challenge’ is more flimsy. A negative becomes a positive, as this action from Raúl Jiménez illustrates.

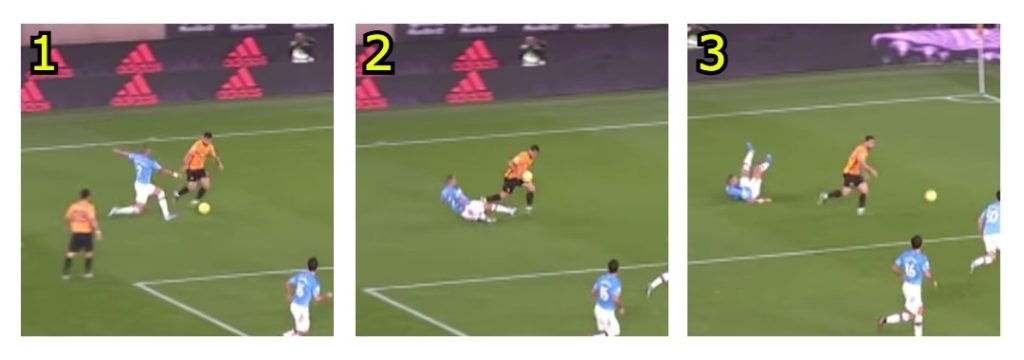

Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Manchester City 2019/20

(see video link to Wolves YouTube channel)

Originally recorded as a ‘Challenge’ by Jiménez, Riyad Mahrez doesn’t escape the attentions of the Mexican and is forced back (images 1 & 2), clearing the ball out of play (image 3).

Since 2015/16 one player stands out among the top ten each season for ‘Challenges’ – Danny Ings.

The only centre-forward named in the 60, his appearance in 2019/20 is perhaps a reflection of Ralph Hasenhüttl’s pressing style and certainly contributed to his 22 goals that term. As this strike against Tottenham Hotspur demonstrates.

A successful tackle and a goal, how many of his 54 challenges came close to replicating that outcome? It’s likely that some would now be recorded as ‘Attempted Tackles’.

Hard to Pin Down

In their efforts to document a game of football, Opta have defined 68 events and created 327 qualifiers to describe those events. A list that is reviewed at least once a season.

But football can be a difficult game to detail precisely, not every action fits neatly into a definition.

Kyle Walker’s effort to tackle Jonny sits between two or three event types.

Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Manchester City 2019/20

(see video link to Wolves YouTube channel)

It was logged as a ‘Challenge’ but, while Walker fails to dispossess Jonny, he does get a foot on the ball, so it could have gone down as a ‘Tackle’. Although a tackle also requires the tackler to “successfully take the ball away from the player in possession”, which he doesn’t.

And it wouldn’t be an ‘Attempted Tackle’ because Jonny is clearly trying to beat Walker – and ultimately his ‘Take On’ succeeds.

Two into one won’t go

Crucially, an event can’t be two things.

Opta data collectors occasionally have to make a decision about which category an event falls into. Is this an interception or an attempted pass by Fernandinho?

Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Manchester City 2019/20

(see video link to Wolves YouTube channel)

The loggers take into account the action of the player, the pressure he is under, and the time he has. The above example went down as a failed pass, rather than an interception, but other similar instances were recorded as interceptions or clearances.

Moments later in the same match, this action was entered as an interception by Fernandinho: he has to react quickly and it’s a definite movement to stop the pass reaching its target. Even though, at the same time, he lays the ball off to a team-mate.

Likewise Eric Garcia simultaneously clears Neto’s cross and directs the ball to Gündogan. This was recorded as a clearance rather than a pass.

Arguably, the difference with the first example is that Fernandinho has more time to consider playing the ball to Benjamin Mendy. But isn’t his action both an interception and a pass?

In a way, Fernandinho is too good. Had his positioning been worse, he may have needed to stretch to intercept the ball or take two touches instead of one. As Leander Dendoncker did when intercepting this attempted through ball from De Bruyne.

So do the stats accurately reflect Fernandinho’s qualities as a footballer?

Since Pep Guardiola took charge of Manchester City not one of their players features among the top ten each season for ‘Tackles’, ‘Clearances’ or ‘Blocks’. In 2016/17 Nicolás Otamendi made the top ten for ‘Interceptions’, the only time a Man City player has been included during the Catalan’s five years at the helm.

So despite defensive midfielders featuring more frequently in ‘Interceptions’ than any other position, Fernandinho doesn’t make the list once.

Although he was among the top ten players for ‘Challenges’ in Guardiola’s first season, suggesting he was either applying pressure to opponents or just not very good at tackling. The Brazilian has a different style to positional peer N’Golo Kanté, whose bustling approach sees him do well in several defensive categories.

If we have the ball, they can’t score.

– Johan Cruyff

Fernandinho’s best metrics reflect the team’s philosophy.

He was among the top three passers for two successive seasons, and in 2017/18 only three players were credited with more ‘Second Assists’: a pass that is instrumental in creating a goal-scoring opportunity. As mentioned in part one, these used to earn assist points in FPL.

With the way on-ball statistics are recorded, positional astuteness is hard to measure, especially in sides that favour possession.

Unseen Skills

Occasionally, the numbers don’t tell the full story.

Bruno Fernandes was key to Mason Greenwood’s goal against Burnley, letting the ball run between his legs. The Portuguese was deserving of an assist but, on this occasion, the fact he didn’t touch the ball meant he went unnoticed in the stats.

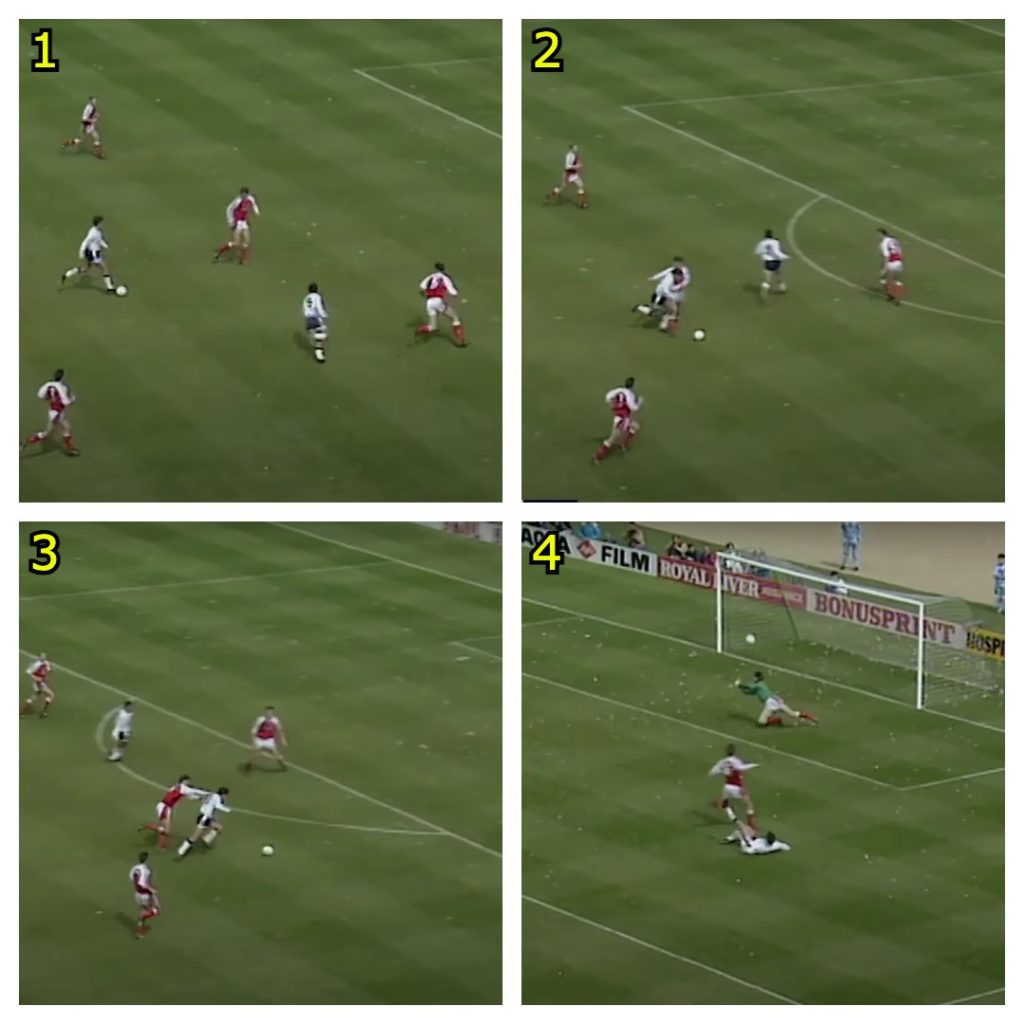

Similarly, a great run from Vinny Samways opened up space for Gary Lineker to score against Arsenal in the 1991 FA Cup semi-final. This might be a rather old example and, admittedly, a match feed XML of the game doesn’t exist, but it did spawn a memorable piece of commentary from the eloquent Barry Davies:

Nayim to the left, Samways ahead. And Lineker uses him by not using him – good try, he’s scored!

Tottenham Hotspur vs Arsenal, FA Cup semi-final, 1990/91

(see video link to the FA Cup YouTube channel)

Unselfish off-the-ball runs, pulling defenders out of position, are invisible to Opta.

From Firmino’s clever movement to create space for Salah or Harry Kane attracting two defenders to make room for Son Heung-min to run in behind, numerous players have had comparable contributions overlooked by the statisticians.

Little moments of skill can also be missed. Bernardo Silva shows good awareness to evade the onrushing Romain Saiss: a quick look over his shoulder before receiving the ball, followed by a sharp turn. But the only events noted are the pass to Silva and the pass he plays to Fernandinho.

Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Manchester City 2019/20

(see video link to Wolves YouTube channel)

Perhaps the question to consider is: what do we want to measure from this action – Silva’s ability to avoid pressure? To retain possession? To progress the ball? And would measuring this action help tell a better story?

Like Jota holding off De Bruyne, it’s not really a ‘Take On’, he’s simply evading a challenge rather than trying to beat his man. Arguably both Silva and Jota are just doing their jobs and is that really noteworthy?

If I have to make a tackle then I have already made a mistake.

– Paolo Maldini

Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Manchester City 2019/20

(see video link to Wolves YouTube channel)

In the next example, Conor Coady does his job defensively when holding off Raheem Sterling. He stayed on his feet and used his body to stop the winger going around him. But he receives no credit for this in the stats. The action is recorded as an ‘Overrun’ by Sterling: a failed dribble that isn’t a duel event.

The irony is that if Coady had been worse at his job he might have been forced to make a sliding tackle, and for this he would have gained credit.

It makes you wonder if the defensive nous of five-times Champions League winner Paolo Maldini would have been largely ignored by on-ball events.

If we want to reward undervalued players in the FPL, we first have to be able to measure their contribution.

But there are new metrics that can highlight their worth.

Chain Reaction

In order to tell a more detailed story of what is happening on the pitch, Opta’s possessions model strings together the discrete events from the match feed XML into sequences.

On a player level, this adds context to recoveries, tackles, and interceptions by looking at what happened at the end of a passage of play.

For instance, Declan Rice is very good at winning the ball and starting a possession sequence that ends in a shot. Perhaps this is something, like creating a chance, that could be rewarded in the Bonus Points System?

Opta-cle Illusion

The aim of this article has been to help you understand, in detail, how Opta sees a match and how that affects FPL.

Perhaps an interesting philosophical question to ponder is – does the way Opta sees a match influence our reading of the game?

The way we talk about football, especially us FPL managers, is filtered through the metrics they produce. We’ve become football cyborgs: our human intuition supplemented by an array of statistical objectivity.

Do we value players because of the way Opta chronicles a match? And is that compounded because of the stats that FPL has chosen to use?

Maybe. Although the headline events of goals, assists, and clean sheets don’t require much interpretation and give you the most points in FPL.

However, make no mistake, stats can be detrimental to the game.

Do I not like that

Charles Reep, the pioneer of football analytics mentioned at the start of this article, went way beyond the Observer Effect with his meticulous note taking.

Reep discovered that most goals come from moves of three passes or fewer. Therefore, he logically concluded that if you want to score more goals, you shouldn’t pass the ball more than three times. Long-ball tactics were born.

But he didn’t question how he could be wrong. He confused correlation with causation and fell prey to confirmation bias: our tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms our existing views or expectations.

… almost everything in soccer involves three passes or fewer, including moves that don’t lead to goals. And if you look at Reep’s own numbers, they show that if you tried a move of three or fewer passes you are actually less likely to score a goal than if you tried more passes. So the secret to scoring more goals was actually the complete opposite of what Reep thought it was.

– Neil Paine, How One Man’s Bad Math Helped Ruin Decades Of English Soccer

Nonetheless, his ideas permeated the upper echelons of the national sport, influencing the likes of England manager Graham Taylor. The FA even produced and distributed a coaching handbook based upon his theories entitled “The Winning Formula: Soccer Skills and Tactics”.

So a man who could have been football’s Bill James is now, sadly, derided by most.

But popular American sports (and cricket) lend themselves more readily to stats. And Reep grasped the unpredictable nature of association football:

The result of the match does not in any way indicate the true merit of the teams concerned. The act of scoring goals is very largely a matter of chance.

– Charles Reep

If he were alive today he probably would have embraced expected goals.

The idea of combining different sources of information into one has always appealed, and we’ve come a long way from the days when Opta was a mere marketing tool, producing an index to rank players.

You will always need people to work with the data – to interpret meaning [and] communicate findings.

– Matthieu Lille-Palette, Senior Vice President of Opta

Not only is it important to understand how stats are coded but also what they tell us.

On a basic level, is a player with a high pass completion percentage a really good player or someone who never takes any risks?

The job of writers and video content producers, and perhaps the secret to being a good Fantasy manager, is to sort the wheat from the chaff.

Combine our external knowledge with the numbers, find the opportunities, recognise the significant moments – be that a formation change, a positional switch or a player hitting form. And yes, form is real and not, as Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman asserted, “a cognitive illusion” – just ask Joshua Miller.

There’s more

The final part of this series will look at the trends of recent seasons, learn why goalkeepers do so well in the BPS for recoveries, and take a look to the future and how tracking data is revolutionising analytics.

3 years, 5 months agoI’ve looked at all the stats from the euros, including tackles and interceptions, and plugged the data into the opts formula. The machine spit out the following conclusion: it’s coming home